Global Issue

Global Issue: Editor’s Letter

Editor’s Letter

John Fraser

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Pundy’s Picks for Conscious Travel

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Genmaicha Martini Recipe

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

The Spread Love Project by Nicholas Konert

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

Wade Davis

Anthropology is the antidote to today’s nativism says the scholar and author

Carla Sozzani

The future of retail according to the founder of legendary concept store 10 Corso Como

The Art of Migration

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

John Pawson

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Amy Duncan

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Sila Sveta

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

David de Rothschild

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Can Fashion Be Sustainable?

Shaping a better world through what you buy – or don’t

Brendon Babenzian

Supreme’s former creative director wants to end the cycle of consumption with his new brand Noah

Lily Kwong

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

House of Yes

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

Vivie-Ann Bakos

DJ Extraordinaire

Chez Dede

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

Jesse Israel

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

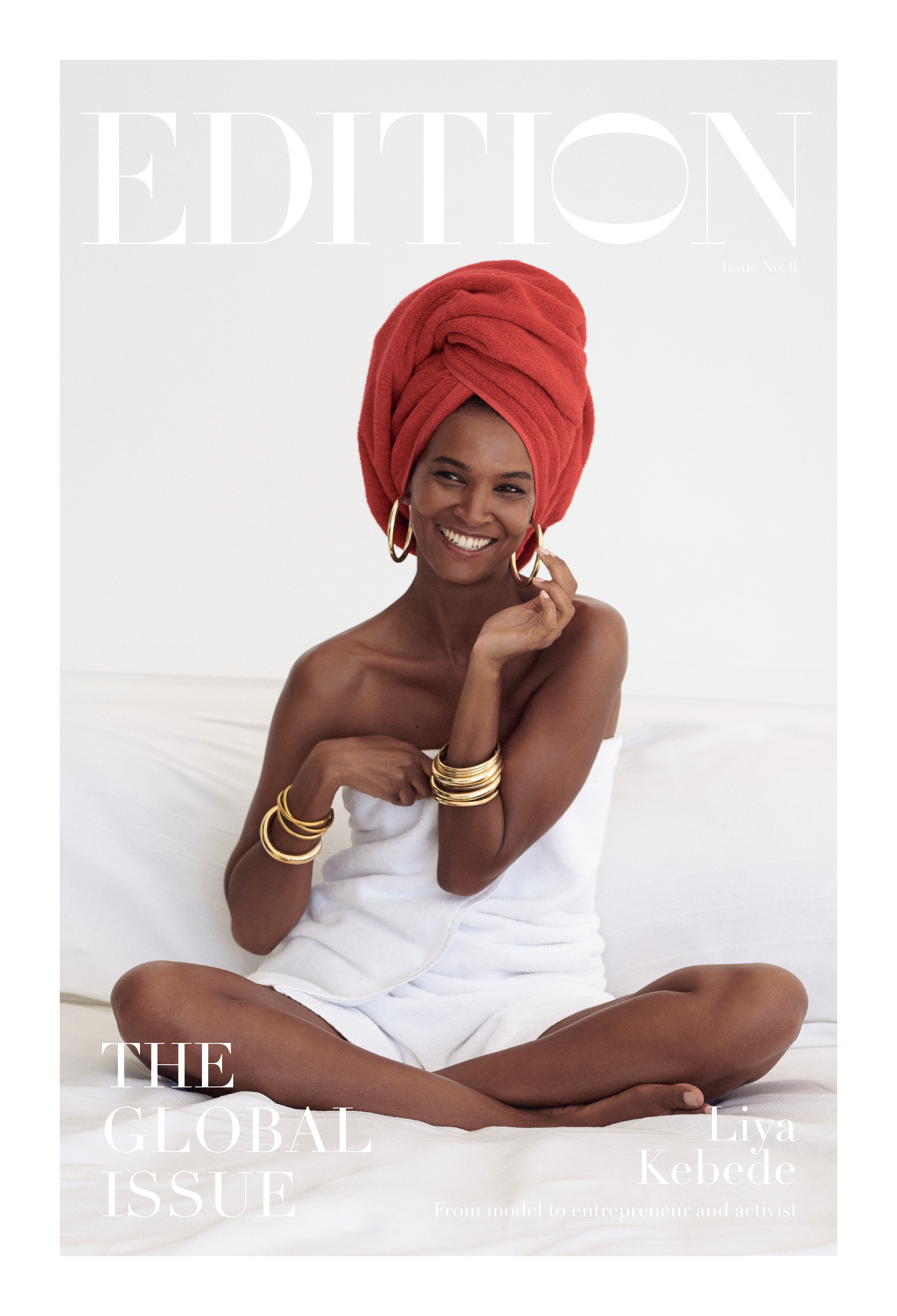

Liya Kebede

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change

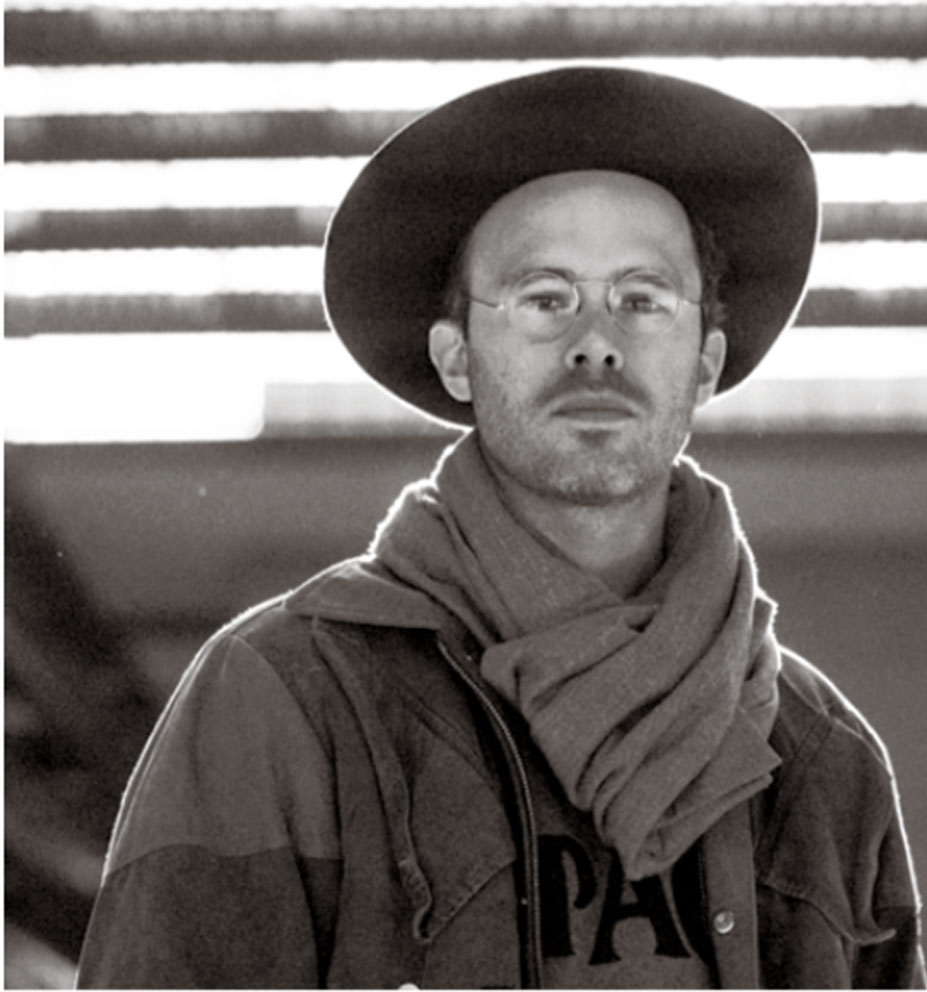

Daniel Arsham

How the Miami-born Artist Is Becoming the Archaeologist of the Future

Stepping into Daniel Arsham’s Greenpoint, Brooklyn studio is like being suspended in various points of time: packed on shelves, tables, and hanging from the ceiling are artifacts from the present (Nikes, Leica cameras, basketballs) that evoke the past (constructed, for instance, from millions-of-years-old glacial rock dust). And to make matters even more meta, Arsham works as though he’s decades into the future looking back.

The Miami-born creator is one half of Snarkitecture, an experimental architecture studio whose collaborators range from Beats by Dre to Calvin Klein. And he’s also one of contemporary art’s most coveted artists, having mounted exhibitions around the world championed by the likes of Usher. To extend his ouever, he launched his own film production company in 2014 and is slowly releasing out his nine-part ethereal film series Future Relic starring Juliette Lewis and James Franco.

Portrait: James Law

I remember trying to reverse-engineer the house I grew up in, being inside of the house and trying to draw architectural plans of that.

When you walk into your studio there’s a sign that reads, “Welcome to the Future.” What is the deeper meaning behind that?

My general feeling about time, and the present, the past, and the future is as malleable as the other materials in which I work. That prompt of “Welcome to the Future” is that each moment in which you arrive is the future. You’ve already arrived at it.

How did the future become an omnipresent theme in your work?

In some ways, part of my interest in the future comes through my sort of obsession with archaeology. But inherently, archaeology is a fiction, right? They can tell us whatever they want, but even after developing all of the stories and the basis for Egyptology, for a long time they still didn’t realize that a lot of stuff was painted. So my position is that we think that we can know the past, but in fact we know the past as well as we know the future.

What kind of materials do you incorporate in your work to tell this narrative?

Volcanic ash; selenite crystal; obsidian, which is a volcanic glass; pyrite; there’s a number of different types of quartz—and that’s just in this kind of sculpture. I also make work in fiberglass and my paintings are made in gouache. There are very few materials that I wouldn’t have some sort of idea to manipulate.

Why is it important to use materials from the past and create new narratives with them?

It’s about developing something that is believable, that feels authentic. Creating something that is trompe-l’oeil—inherently the fiction falls apart more quickly. The first work I made was an old camera cast in ash: I brought some [volcanic] stones back from Easter Island with me, crushed those up and that became the first work. It looked so real and it felt so real. In some ways, these figure works that I’ve been making more recently recall the famous figure from Pompeii. We can tell they’re contemporary because they’re wearing Nike, yet they appear as if we’re viewing them from the future.

With your mind fixed in the future, is it hard to stay in the present? Does having a child help?

Yeah, I have a two-and-a-half-year-old son named Caspar. He’s very immediate. I think that his influence on me is as kind of a different way of looking at things. I’ve often incorporated, even before his birth, ideas that were related to how a child might interpret the world. I try to cause scenarios where people misrecognize architecture; where scenarios that might otherwise be very rigid and fixed can become malleable and fluid. Children often use things in the wrong way: they use a knife as a spoon, they may use a handrail as a play toy. That kind of misrecognition of architecture can be helpful for creating new elements and new experiences.

Kids have so much imagination, then as we become adults we learn to tone it down, to—to unlearn. I never got there…

So many people do though. How do you tap back into imagination?

Even before my son was born, a lot of the work I made didn’t obey those rules. It played with people’s expectations of the existing world, whether that be through the decaying of something that you know, or the manipulation of architecture. The running theme through all of that is this idea that we can make things act in ways they shouldn’t. That transformation of the everyday and of architecture can be uncanny, can be transformative, can make little kids run away in fear.

You work as both an artist and as one half of the creative duo Snarkitecture. How do you approach a project differently whether for a gallery or a client commission?

A lot of the stuff I make has no place in architecture land. That’s kind of the reason why Snarkitecture started. [Years ago] I was making something that had been previously shown in a gallery and museum context and it was being commissioned for a public space. It got to the architect who was building the space, and he said, “There’s no way that this is happening, this doesn’t meet any building code.” So I worked with Alex [Mustonen] to bring that project into compliance with all of these other sorts of necessities, and Snarkitecture was born.

Do you remember the first building you ever saw that sparked your interest in architecture?

I remember trying to reverse-engineer the house I grew up in, being inside of the house and trying to draw architectural plans of that. To this day I could probably draw a very accurate floor plan of the house that I grew up in, even though I haven’t been there in 20 years.

Where does the name Snarkitecture come from?

The name is based on a Lewis Carroll poem called “The Hunting of the Snark,” which is a story about a bunch of idiots searching for a beast called the snark. All they have to go on is a blank, white map.

Which is fitting because you’re colorblind. But I heard you’ll soon be getting special glasses that will help you see in color—i didn’t even know that they had glasses like that.

They have not had them for long. A couple of years ago, these scientists who were developing specialized lenses for laser use—for surgery and things like this—discovered this refraction that was happening with the lenses. Being colorblind doesn’t mean that you don’t see any color: what it means is the rods and cones in the eyes can not distinguish the difference between colors, especially when they have a similar wavelength. What these lenses do is separate the wavelength of light more drastically so it increases the difference between colors.

How do you think that will change your practice?

Right now, I don’t feel like there’s anything missing. But being introduced to that, maybe I’m going to hate it, just be like, “I can’t believe that this is the world that you guys all see!”

Your hometown of Miami may certainly feel more vibrant in color. How was it growing up as a creative person there?

I grew up among a kind of tropical forest landscape. I spent a lot of time out in the Everglades and out on the water, so the Miami that everyone imagines now with partying and South Beach—that was not at all part of my childhood.

Was there much of an art scene growing up?

I left Miami in 1998 to come to New York to go to school. I studied at Cooper Union. After school I went back to Miami for a while and, with a couple of friends, started an exhibition space called The House. That was right around the time that Art Basel was beginning. It was a time when people would still visit artists’ studios in Miami. There weren’t the dinners and parties and all of this other stuff that’s going on now in Miami—it was a very particular moment in time.

You wanted to delve into film, so you recently started your own film production company?

I have been making these objects which are very evocative, these kind of future relic pieces that were often being written about in ways that recall the story. People would ask, “What is the universe that you imagine these objects existing within?” And so I wrote that as a treatment. Some people I knew that worked at Tribeca Films encouraged me to develop that into a script, and it went from there. In order to make films you’ve got to have a production company, so I started Film the Future to work on that and some other smaller projects.

Why was it important for you to work in film at this point?

Film is something that I’ve always been interested in. It is, for me, the kind of complete universe that encapsulates all the other areas in which I work: architecture, scenography, photography. All the props in the film are things that I’ve actually made, and it allows me to bring all those together into one sort of universe.

In Future Relic 03—the third installment of your first film—Juliette Lewis is holding a newspaper dated 2052. In the year 2052, do you really think newsprint will be a relevant medium?*

You never know. According to 2001: A Space Odyssey, we’re living on the moon right now. So we’re still reading newspapers—there are certain things that just won’t change. Part of what I love about depictions of the future are when they feel very real and pedestrian. I try to combine elements of the present to allow viewers to feel like it’s not so removed from their everyday life.

*This paper you hold in your hands is, of course, timeless

You’re highly prolific on Instagram and Snapchat; it’s almost become an extension of your artwork. What’s so great about your engagement on there is that it’s the one place your followers really get a glimpse inside your head.

I think that the most powerful thing about it is that it enables me to reach audiences that wouldn’t otherwise go to a gallery or to a museum. It reaches people in places where they may not have access to that. I find that to be a very egalitarian way to show work.

Why is art important?

Artists are tasked with uncovering things that people don’t pay attention to, that they maybe otherwise should, and provoking responses that are outside of people’s everyday experience. I think that that can have a huge impact on people in general, on society, and obviously culture.

Art & Culture

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

Experiences

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

Food & Drink

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Personalities

Style

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change