Global Issue

Global Issue: Editor’s Letter

Editor’s Letter

John Fraser

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Pundy’s Picks for Conscious Travel

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Genmaicha Martini Recipe

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

The Spread Love Project by Nicholas Konert

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

Wade Davis

Anthropology is the antidote to today’s nativism says the scholar and author

Carla Sozzani

The future of retail according to the founder of legendary concept store 10 Corso Como

The Art of Migration

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

John Pawson

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Amy Duncan

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Sila Sveta

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

David de Rothschild

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Can Fashion Be Sustainable?

Shaping a better world through what you buy – or don’t

Brendon Babenzian

Supreme’s former creative director wants to end the cycle of consumption with his new brand Noah

Lily Kwong

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

House of Yes

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

Vivie-Ann Bakos

DJ Extraordinaire

Chez Dede

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

Jesse Israel

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

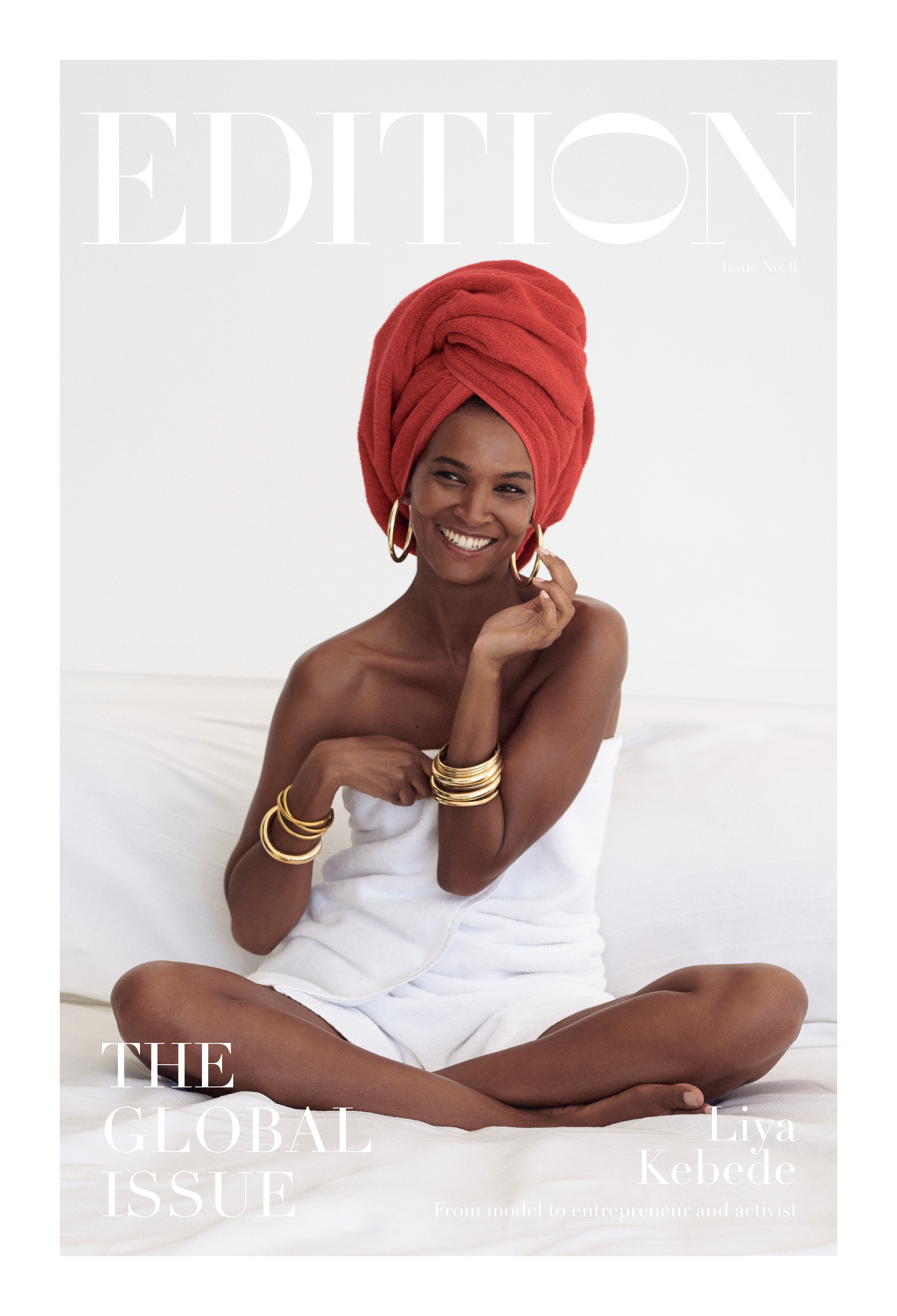

Liya Kebede

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change

Just days before the Whitney Museum of American Art opened its new 200,000-square-foot space in the Meatpacking District, we sent everybody’s favorite man-about-town and Half Gallery owner Bill Powers to get a glimpse. He spoke to Scott Rothkopf, who joined The Whitney in 2009 as their youngest curator ever. He’s since organized some of this century’s most important exhibitions by artists like Wade Guyton, Glenn Ligon, and last year’s knockout Jeff Koons retrospective—the last show in the museum’s Uptown galleries.

Bill Powers: The Whitney’s opening show is installed chronologically from the top down…

Scott Rothkopf: We have about 650 works of art from our collection on view. In the lobby gallery there is a small presentation about the founding of the museum. After that, yes, the show begins on the eighth floor in our skylit galleries with pieces from the early 20th century. We installed it this way because the floor plates grow as do the ceiling heights as you move down, which often reflects the scale of the art being made as you get closer to the present.

The new Whitney Museum has something like 13,000 square feet of outdoor space for sculpture?

On four terraces, yes. In our opening season, we will have sculpture from the permanent collection on a few terraces and another large terrace dedicated to a site-specific installation by Mary Heilmann.

You’ve organized several outstanding solo surveys over the years. In The Whitney’s first exhibition in its new building, “America Is Hard to See,” will you include pieces by artists like Wade Guyton as a nod to recent solo exhibitions you organized?

This exhibition nods to several histories layered on top of one another: one is the history of American art; another is the history of our collection; and finally there’s our own exhibition history whether it’s the “Black Male” show from 1994, our many biennials, or a survey like Guyton’s. We’re including him with a painting he gave the museum that has never been shown before.

Jeff Koons once told me that engagement is a driving principle in both his art and his life. I mention it because you curated his retrospective at The Whitney last year.

That’s so true of Jeff’s perspective today. He used to talk about Duchamp and his fascination with the readymade. Now he’s interested in older art and he talks more about Picasso, I think, because Picasso had a very active studio life – and love life – until he died, whereas Duchamp is thought of as a guy who quit making art and was somewhat disengaged from society later on. Jeff probably doesn’t relate as much to that image of an artist at this point in his life. But I’m not a psychiatrist.

Coming here today, I walked by Diane Arbus’ old apartment building. You forget sometimes that the neighborhood has such history.

There are a lot of works in our first show, “America Is Hard To See,” that make reference to the surrounding area either speci cally or more abstractly. We have a whole gallery about the AIDS crisis including a picture of David Wojnarowicz photographed by his boyfriend and mentor Peter Hujar. There’s a painting by Florine Stettheimer of the Statue of Liberty

in the harbor. And we have George Bellows’ picture of ice flows on the Hudson adjacent to a window overlooking the river, which feels incredibly familiar after the winter we just experienced in New York.

Your transition downtown is a sort of home- coming, too, since The Whitney Museum’s first outpost was on Eighth Street.

Yes, we’re not that far from our original location. Also, so many artists were situated here. Roy Lichtenstein had a studio on Washington Street for the last part of his life.

And he famously ate lunch every day at the Meatpacking district institution, Florent.

We actually have a Charles Atlas video in our collection that was partially shot there.

When I did a preview tour of the new building, I noticed you and a few other museum curators looking at paint colors for the gallery walls. What did you decide on?

For the majority of the spaces we’re using decorator’s white which has a touch of gray in it. And we’ve added accent colors. We have an incredible room about spectacle in mid- century New York—nightlife scenes—where the walls are almost a midnight blue to create a sense of drama. There are some pictures from the 1930s and 1940s which we’ve hung on dark brownish gray walls, since many of these works were made to be seen in interiors that weren’t bright white. For example, we have an Andrew Wyeth painting of a crow lying in a eld, and on a white wall it looks out of place and you end up noticing the frame a lot more. The taste that informed the frame also informed the architectural settings the painting might have been made or seen in. But we’re coming to terms with the fact that our new building is from yet another time and we’re reconsidering elements like wall color and framing in a new light. It’s like showing up at a family reunion and all of these beloved relatives look a little bit different than how you remember them.

Do you think about how the evolution of technology can change the way a work is perceived decades later? For instance, I wonder how a Josh Kline installation comes across in the year 2050?

When oil painting was first invented it was thought of as a new technology. We have a lot of work in our collection which maps to technological changes in the 20th century, whether it’s television sets from the 1960s in sculptures by Nam June Paik or neon tubes in a Keith Sonnier. Then there are things people might not identify as new technology like the finishes on a John McCracken or a Donald Judd which were groundbreaking in their time as new industrial materials.

The Art Newspaper recently reported that a third of all museum solo shows are with artists represented by only five galleries. Does this statistic seem troubling to you?

That may be true, but in general I think people tend to see conspiracies where they want to find them. I remember when I worked for Artforum, people would say oh, the big advertisers get all their artists on the cover. And big galleries like Gagosian did have multiple covers, but then others like, say, Greene Naftali had artists on the cover without ever having placed a full-page ad.

“THERE’S A REAL RISK WHEN YOUR AMBITION OUTWEIGHS YOUR TALENT OR SKILL SET. IN THE END YOU HAVE TO DELIVER.”

I asked art critic David Rimanelli who the greatest museum curator of all time was. He said it’s a tie between the Guggenheim’s Robert Rosenblum and Swiss curator Harald Szeemann.

I think a lot about William Rubin from MoMA who got a bad rap for being imperious and conservative, but the quality of his scholarship and the rigor of his shows was so admirable, as was the laser-like focus he brought to building the collection.

You curated a Mel Bochner show while still a student at Harvard. Do you think there’s ever a downside to being so ambitious?

There’s a real risk when your ambition outweighs your talent or skill set. In the end you have to deliver.

Can you remember the first piece of art that had an impact on you?

I was obsessed with Calder’s “Circus.” I remember my grandparents taking me to The Whitney as a little boy and seeing it in the museum lobby. I went home to Dallas and made a whole collection of circus characters in my garage with bent coat hangers and a soldering gun.

Have you ever experienced Stendhal Syndrome, you know, becoming extremely emotional while looking at a painting?

It happens to me more often with abstract art, which surprises me. I remember being in college and seeing Ellsworth Kelly’s retrospective at The Guggenheim and being brought to tears. There was something so beautiful and intense about encountering his vision as a total environment in [Frank Lloyd] Wright’s architecture.

What motivates you, Scott?

I know this sounds obvious, but I love art. In terms of working with artists, I imagine myself almost like a lawyer arguing their case to the public. And if I do my job right, you shouldn’t see my hand.

Art & Culture

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

Experiences

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

Food & Drink

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Personalities

Style

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change