Global Issue

Global Issue: Editor’s Letter

Editor’s Letter

John Fraser

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Pundy’s Picks for Conscious Travel

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Genmaicha Martini Recipe

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

The Spread Love Project by Nicholas Konert

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

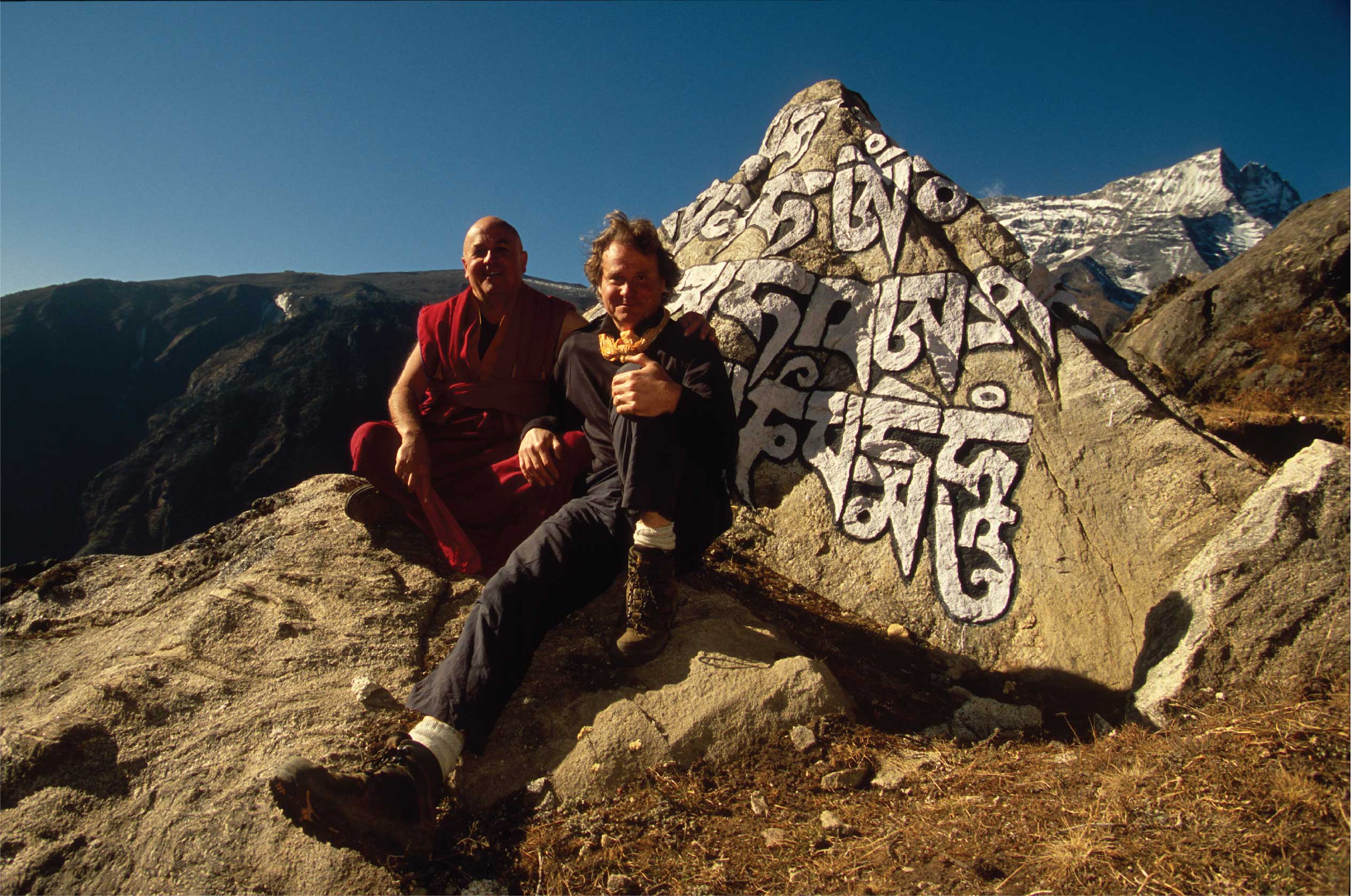

Wade Davis

Anthropology is the antidote to today’s nativism says the scholar and author

Carla Sozzani

The future of retail according to the founder of legendary concept store 10 Corso Como

The Art of Migration

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

John Pawson

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Amy Duncan

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Sila Sveta

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

David de Rothschild

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Can Fashion Be Sustainable?

Shaping a better world through what you buy – or don’t

Brendon Babenzian

Supreme’s former creative director wants to end the cycle of consumption with his new brand Noah

Lily Kwong

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

House of Yes

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

Vivie-Ann Bakos

DJ Extraordinaire

Chez Dede

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

Jesse Israel

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

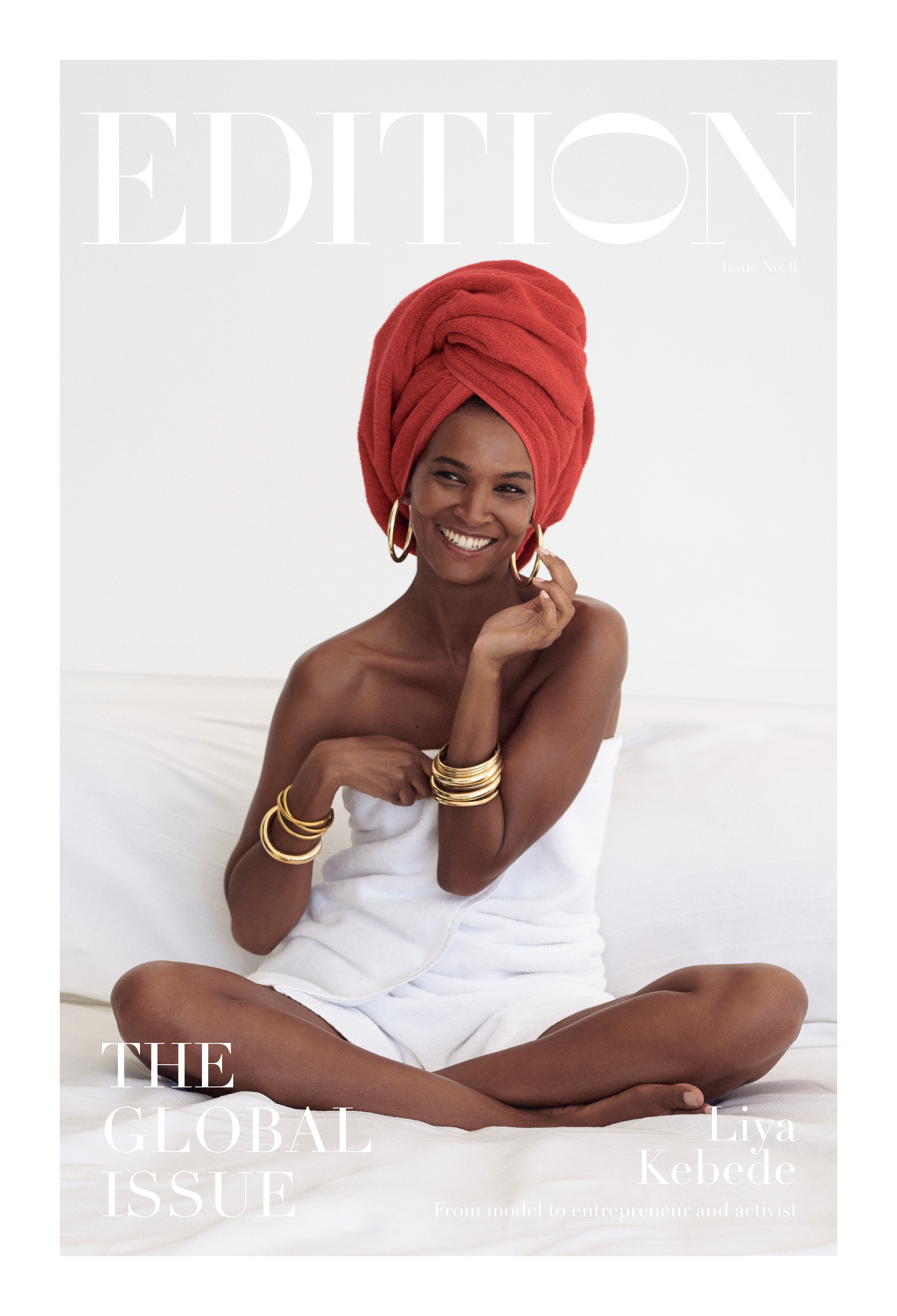

Liya Kebede

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change

The message of anthropology is that each culture has something to say and deserves to be heard. Anthropology is the antidote to the nativisim of today.

Wade Davis was only fourteen years old when his mother, convinced that Spanish was the language of the future, diligently saved enough money to send him from Canada to Colombia on a school trip. “I found myself living for eight to ten weeks surrounded by the intensity that was so alluring of the Colombian people, unlike any I’d ever known,” he says. “A lot of the older Canadian boys on the trip became homesick but I felt like I’d finally found home.”

That trip ignited Davis’ enthusiasm for exploration. After his return to North America, he went on to enroll at Harvard, where he obtained his master’s degree in anthropology and his PhD in ethnobotany, the study of the traditional knowledge and customs of a people concerning plants and their religious and medical uses. Now 65, Davis has devoted his life to travel and discovery and shares his experiences through several mediums: He has authored over twenty books, his photography has been displayed in places such as the United Nations, he narrates his adventures in several films, and he travels the world as a lecturer. The former explorer-in-residence at the National Geographic Society is also a tenured professor at the University of British Columbia and sees anthropology as a way to unify our world. “The whole purpose of anthropology is to make the world safe for human differences,” he says.

“The message of anthropology is that each culture has something to say and deserves to be heard. In many ways, anthropology is the antidote to the nativism of today.”

In an effort to communicate the importance of his field to modern society, Davis coined the term ‘ethnosphere.’ Created to parallel the ‘biosphere,’ the concept highlights how ethnodiversity is under the same or even greater threat than the loss of biological diversity. The situation is troubling to Davis, who says that by homogenizing our cultures we’re losing the opportunity to learn more about

ourselves and each other. “Geneticists have finally proven that we’re all descendants of the same people who walked out of Africa 65,000 years ago

and the important thing is that we’re all cut from the same genetic cloth,” he says. “The point is that there is no hierarchy of culture, the word ‘primitive’

has no meaning. The other peoples of the world aren’t failed attempts at being modern, they’re not failed attempts at being us. Every culture is a unique answer to a fundamental question: What does it mean to be human and alive? The biggest curse of humanity has been cultural myopia, the idea that my world is the real world and everybody else is a failed attempt at being me.”

Despite our loss of diversity, Davis cautions against becoming too demoralized, saying he sees

“pessimism as an indulgence and despair an insult to the human imagination” and instead arguing that we should find optimism through education and experiences. “My father always said very simply, ‘You have to make a decision about what side you’re going to be on and don’t have any expectations of ever illuminating the darkness, but you need to try to be a beacon of light.’ That’s a very good attitude because that means you never expect to win,” he says. “Like a pilgrim’s path, it’s not the destination, it’s a process—the path is the destination.”

When Davis first joined the faculty at the University of British Columbia in 2014, he did so with the condition that he would only teach an anthropology course to the freshman class. Explaining that those are the students who are full of life and flexible in their desire to learn and not yet concrete in any ideologies, he chooses to run his course as more of a celebration of culture, eschewing a traditional note-taking format. “The biggest lie that’s taught to kids all through school is that life is linear,” he says. “Life is made up of a series of crossroads, a series of moments, and what you want to do is cultivate inside of yourself a kind of inner compass so that when you come to the crossroads, you’re making your own choices. I certainly never had any idea what I wanted to do, but I was incapable

of compromise. And I only had one word in my vocabulary, yes, to any new experience.”

Carla Sozzani

The future of retail according to the founder of legendary concept store 10 Corso Como

Art & Culture

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

Experiences

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

Food & Drink

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Personalities

Style

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change