Global Issue

Global Issue: Editor’s Letter

Editor’s Letter

John Fraser

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Pundy’s Picks for Conscious Travel

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Genmaicha Martini Recipe

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

The Spread Love Project by Nicholas Konert

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

Wade Davis

Anthropology is the antidote to today’s nativism says the scholar and author

Carla Sozzani

The future of retail according to the founder of legendary concept store 10 Corso Como

The Art of Migration

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

John Pawson

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Amy Duncan

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Sila Sveta

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

David de Rothschild

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Can Fashion Be Sustainable?

Shaping a better world through what you buy – or don’t

Brendon Babenzian

Supreme’s former creative director wants to end the cycle of consumption with his new brand Noah

Lily Kwong

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

House of Yes

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

Vivie-Ann Bakos

DJ Extraordinaire

Chez Dede

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

Jesse Israel

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

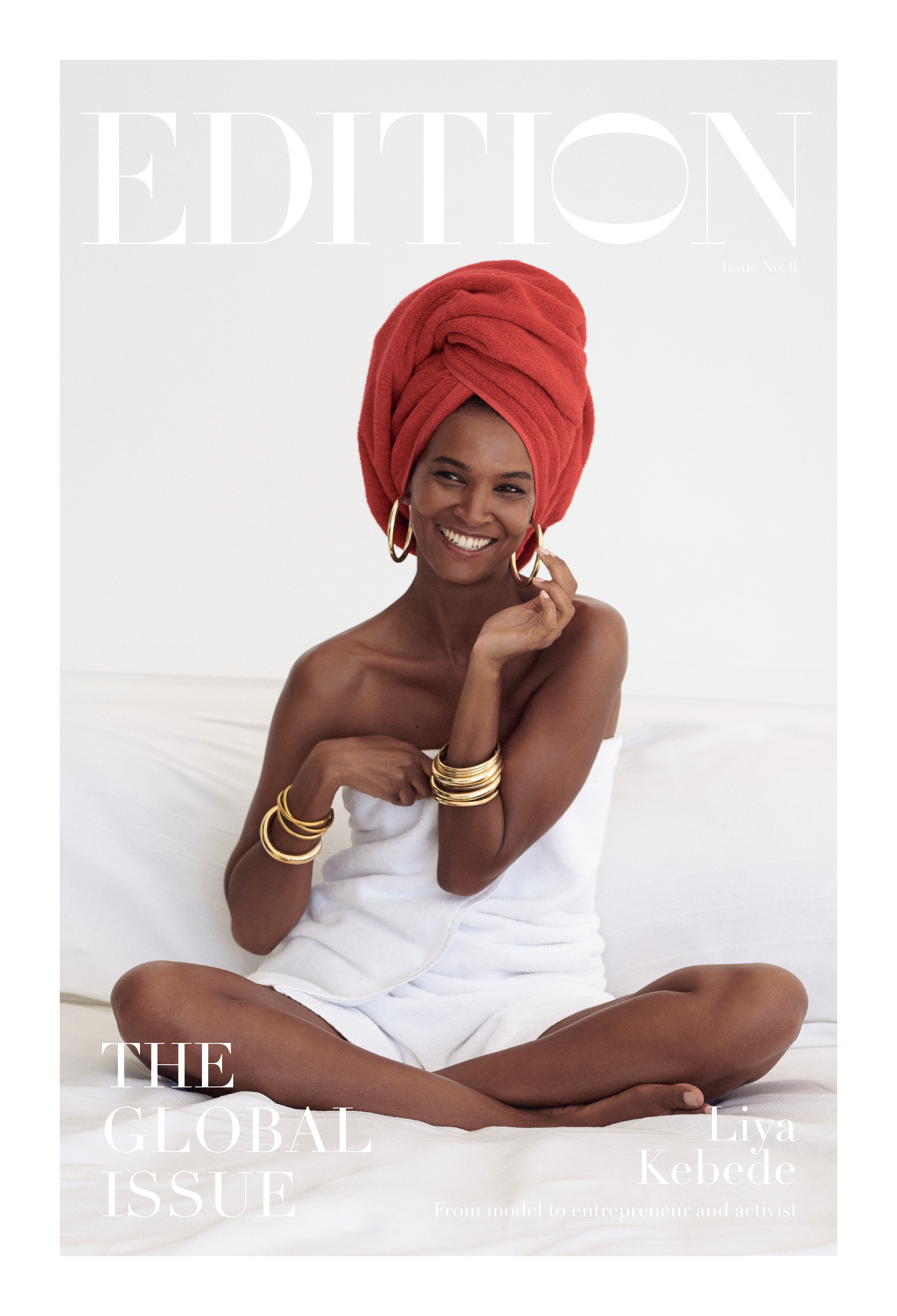

Liya Kebede

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change

hen she arrived in Gombe, Tanzania in 1960, intent on studying chimpanzees, Dr. Jane Goodall was already a trailblazer. As a 26-year-old female naturalist, she was challenging then prevalent stereotypes among her fellow humans. Within a short period of time, her discoveries revolutionized our understanding of apes—their social structures and their ability to use tools—but also challenged fundamental notions about humans’ place in nature. Goodall’s impact has grown beyond her landmark anthropological work. Though she did not set out to be an environmentalist, her significance to the movement cannot be understated, through her activism on behalf of conservation, sustainable economic development, and food production. The founder of the Jane Goodall Institute, she is also a UN Messenger of Peace and Dame Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, and started Root & Shoots, a global network of young people involved in hands-on programs for the community, animals, and the environment. We may be the smartest ape, but Goodall’s ongoing research and the outsize impact of her activism shows that we still have a lot to learn—and most importantly, that we have the tools to make a difference.

hen she arrived in Gombe, Tanzania in 1960, intent on studying chimpanzees, Dr. Jane Goodall was already a trailblazer. As a 26-year-old female naturalist, she was challenging then prevalent stereotypes among her fellow humans. Within a short period of time, her discoveries revolutionized our understanding of apes—their social structures and their ability to use tools—but also challenged fundamental notions about humans’ place in nature. Goodall’s impact has grown beyond her landmark anthropological work. Though she did not set out to be an environmentalist, her significance to the movement cannot be understated, through her activism on behalf of conservation, sustainable economic development, and food production. The founder of the Jane Goodall Institute, she is also a UN Messenger of Peace and Dame Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, and started Root & Shoots, a global network of young people involved in hands-on programs for the community, animals, and the environment. We may be the smartest ape, but Goodall’s ongoing research and the outsize impact of her activism shows that we still have a lot to learn—and most importantly, that we have the tools to make a difference.

Your work has transformed our understanding of both chimpanzees and humans’ position within the animal world. How has your own understanding of chimpanzees evolved since you first began studying them?

When I began studying chimpanzees in 1960 nothing was known about their behavior in the wild. No one had studied them at all. We knew behavior only from captive chimpanzees. I knew they were highly intelligent from reading The Mentality of Apes, a wonderful book by Wolfgang Kohler, who studied a captive colony. My research at Gombe reaffirmed all that I learned from that book.

Was your early interest in anthropology driven by an interest in understanding chimpanzees or understanding the human ape?

I wanted to live with wild animals and write books about them from when I was 10 years old. Few women were scientists in those days. It was after saving up to go to Kenya for a holiday with a school friend that I heard about the late Dr. Louis Leakey, a paleontologist and anthropologist, and arranged to meet him. It was he who got the money for me to start my study at Gombe National Park in Tanzania. (It was Tanganyika back then.) And he was interested in how learning about the behavior of our closest living relative might help him to better understand how our Stone Age ancestors might have lived. At that time, I had not even been to college.

What is a simple lesson that human society can learn from chimpanzee society?

That we humans are not as unique as we once thought. We are not the only beings on the planet with personalities, minds capable of rational thought and, above all, emotions. (I had already learned that from my childhood teacher: my dog, Rusty.)

For more information on Dr. Goodall’s efforts, visit

janegoodall.org and rootsandshoots.org.

Are there lessons humans can learn from chimpanzees about how to be better to each other?

Chimpanzees are very good at conflict resolution. My grandmother used to say, “let not the sun set on thy wrath,” and a subordinate chimpanzee will even beg for a reassuring pat or embrace after being threatened or attacked. There is also a lot I have learned about being a good mother. Good chimpanzee mothers are protective, but not over-protective, affectionate, playful…but above all supportive.

What is the funniest thing you’ve observed chimpanzees doing?

Chimpanzees use long sticks to feed on vicious, biting army ants. They stand back from the nest, dip in the tool, sweep the stick with a mass of biting ants through their hand and eat them as fast as possible. After a few minutes the ants swarm out towards the chimpanzees and they run off. As an adolescent, [a chimpanzee Goodall named] Freud found a place on a vine slung between two trees right above a nest. Ah ha! He had the perfect solution. No ants found him. But oh dear, suddenly the vine broke and he landed right into the nest!

What led you to become a vegetarian?

Cows, pigs, poultry etc.—just because they are domestic animals does not mean they do not have personalities and feelings. When I next looked at meat on my plate, I thought: this symbolizes Fear, Pain, and Death. From that moment I stopped eating all meat, and that includes fish. Later, I learned about the devastating effect that the huge increase in meat consumption is having on the environment. Destroying environment to grow grain—more grain is grown to feed animals than people! Much more water is needed to change vegetable to animal protein. And finally, the harm to human health caused by having to give these wretched animals antibiotics, just to keep them alive in their horrendous conditions, so that bacteria are becoming increasingly resistant to more and more antibiotics, leading to superbugs.

The past decade has been very economically positive for much of Africa. Is development a threat or an opportunity?

If development proceeds in the right way it is very positive. Poverty is one of the huge problems we have to solve. If you are desperate to grow food for your family, or to sell charcoal, you will cut down the last trees, even knowing that this can lead to desertification. Our Jane Goodall Institute program TACARE, which means “Take Care,” has encouraged development in 70 villages in chimpanzee habitats in Tanzania in such a way that people and the environment are living in harmony. Microcredit for groups of women has enabled them to develop environmentally sustainable projects, such as tree nurseries, shade-grown coffee farms, and so on. We provide eagerly accepted family planning information and we provide as many scholarships as possible to keep girls in school past puberty.

As women’s education improves around the world, family size tends to drop. Volunteers from the villages learn to use smart phones to monitor the health of their village forest reserves and the information is uploaded to Global Forest Watch. Forests have since returned to what were bare hills. The people have become our partners in conservation, which is not only beneficial to the chimpanzees and other wildlife, but to future generations of animals and humans alike. We have started similar programs in six other African countries around chimp habitats.

What would you say is the number one conservation priority?

It is tempting to simply say climate change, but there are so many factors that have led to climate change, all interconnected. Forests and oceans are best described as “the lungs of the world”—both give out oxygen and absorb carbon dioxide, the most plentiful of the so called “greenhouse gases,” forming a blanket around the globe, trapping the heat of the sun.

What can we as individuals do to help with conservation efforts?

There is definitely increased awareness around the world of the harm we are doing to the planet. We are using up finite natural resources, in some cases faster than Mother Nature can repair them. When people think about all this, they feel helpless, hopeless. So they do nothing. It is desperately important to realize that every day we live, we make some kind of impact. And we can choose what kind of impact we will make, if we just think about the little choices we make. What we buy. What we eat. What we wear. Where did it come from? Was animal suffering involved? Was it made using child slave labor? Is that why it is cheap? Do we actually need it? If we start making ethical choices and think about the effect on future generations, we shall move towards a better world. We can also make donations to conservation efforts on the ground in different parts of the world. We can volunteer our time and expertise to such organizations. We can spread awareness

Art & Culture

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

Experiences

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

Food & Drink

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Personalities

Style

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change