In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Global Issue

Global Issue: Editor’s Letter

Editor’s Letter

John Fraser

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Pundy’s Picks for Conscious Travel

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Genmaicha Martini Recipe

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

The Spread Love Project by Nicholas Konert

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

Wade Davis

Anthropology is the antidote to today’s nativism says the scholar and author

Carla Sozzani

The future of retail according to the founder of legendary concept store 10 Corso Como

The Art of Migration

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

John Pawson

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Amy Duncan

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Sila Sveta

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

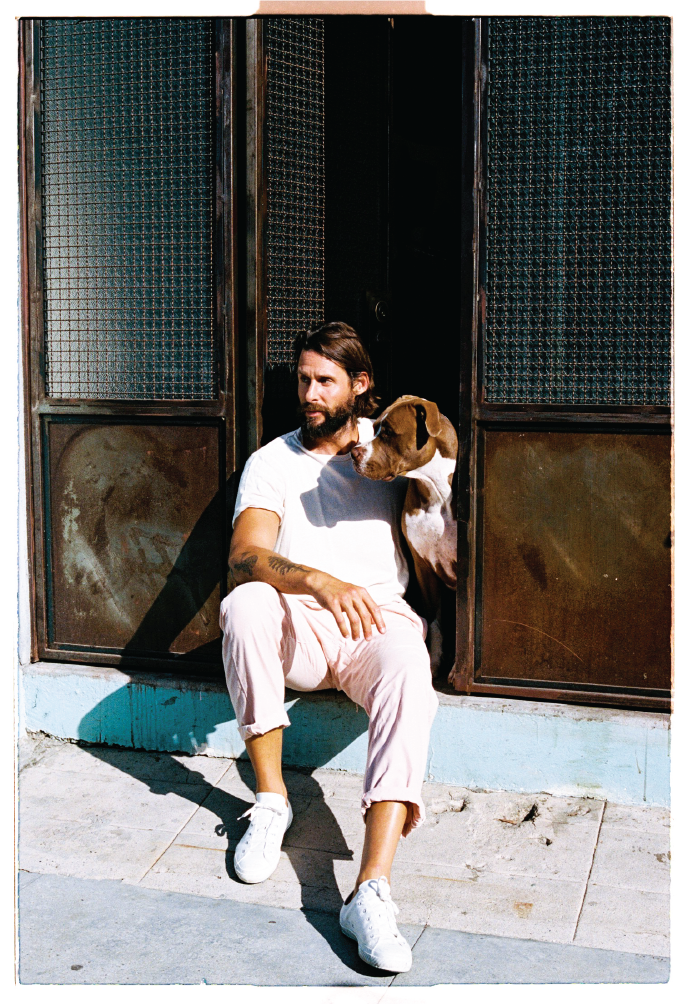

David de Rothschild

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

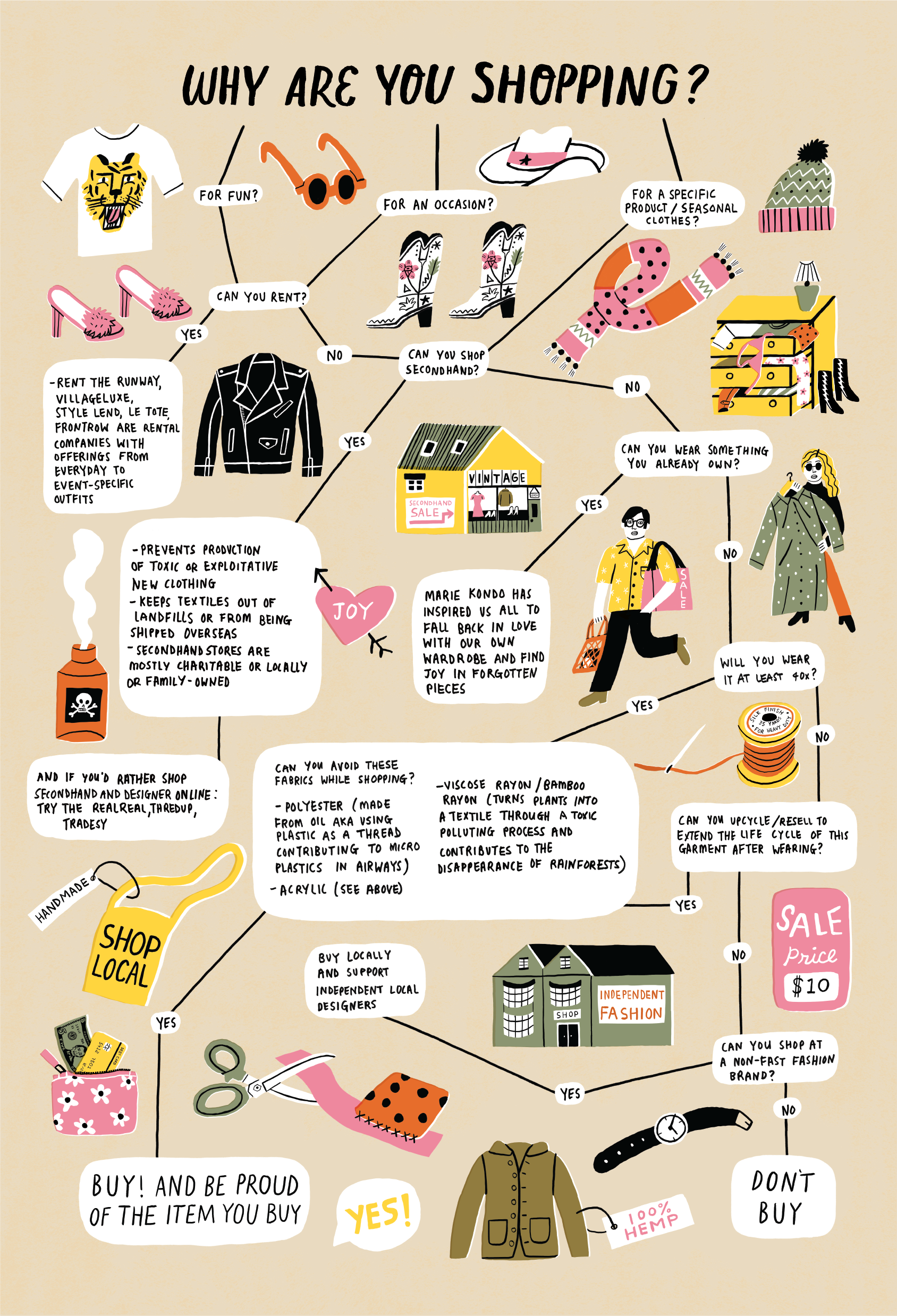

Can Fashion Be Sustainable?

Shaping a better world through what you buy – or don’t

Brendon Babenzian

Supreme’s former creative director wants to end the cycle of consumption with his new brand Noah

Lily Kwong

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

House of Yes

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

Vivie-Ann Bakos

DJ Extraordinaire

Chez Dede

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

Jesse Israel

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

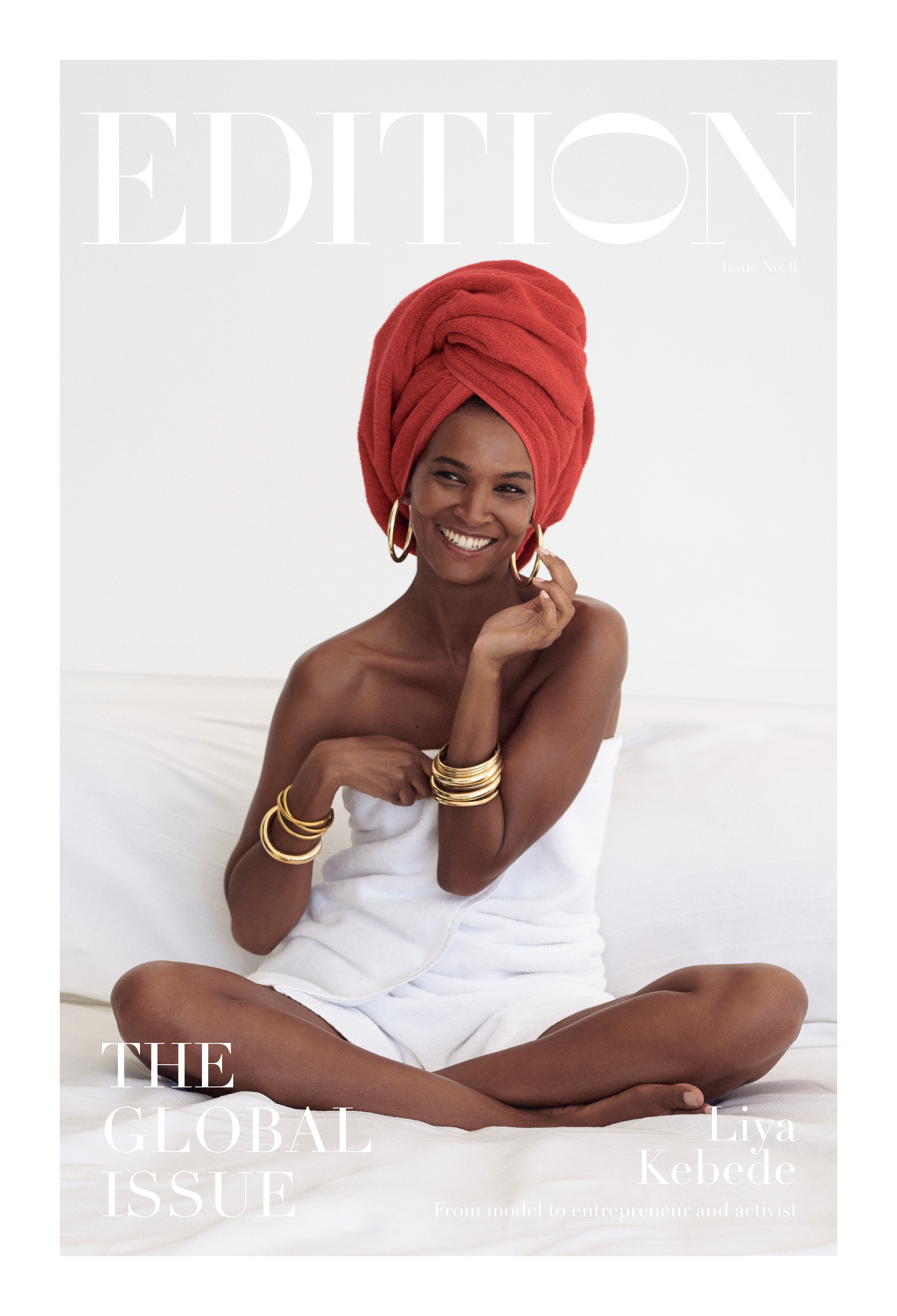

Liya Kebede

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

David de Rothschild

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

By Gautam Balasundar

@david.de.rothschild

Photography by James Wright

A decade ago, David de Rothschild made a voyage across the Pacific on a catamaran called Plastiki, made out of reused plastic bottles. He had already established himself as an “adventurer” ever since his first major expedition as a young man trekking across Antarctica, but this trip was different. His passion had grown from traversing nature to finding ways to preserve it, and the journey across the Pacific was done only to bring attention to the now-infamous Great Pacific garbage patch. He’s pursued this path in the years since, transforming from the classic adventurer to the modern explorer, looking not to dominate nature but to understand it and tell its story. Rothschild still possesses an innate desire to travel to the corners of the world, but he now

does so in the name of his true calling: serving as a voice for the environment. He’s written books, made documentaries, launched the sustainable label The Lost Explorer, and founded the Sculpt the Future Foundation, each experience satisfying his curiosity towards our planet and inciting the same in others. Rothschild is constantly willing to ask questions and seek out any new way to create awareness, challenging individuals, companies, and entire systems to see the endless beauty of nature the way he has through his worldly eyes.

You’ve been on so many incredible journeys and

adventures around the world. Did you always possess this adventurous spirit?

As a kid, I was definitely hyperactive and curious, running around with a lot of energy. I think it was Ogden Nash who said, “You are only young once, but you can stay immature indefinitely,” and I think that sums me up. I’ve always been curious and asking questions. You get older and you don’t ask questions because it can sometimes be seen as embarrassing if you don’t know something, but I think challenging the status quo has to come from asking those questions. It has to come from challenging the ‘that’s just the way we’ve done it’ mentality and that’s something that always excites me.

How did your early voyage to Antarctica shape your view of exploration?

I think for our own romantic idea of exploration, we paint a picture of what we want it to be and if you don’t play into that idea—it’s life or death, it’s man versus nature, it’s the extremes that you’re in—then somehow you’re disappointing the people you’re engaging with and you’re not sticking to the explorer’s code. You must tell everyone how amazing you are or how you conquered that mountain or

how you crossed that ice cap and you lost all this weight and you got all these blisters and were miserable every day and could barely eat by the end or had no sleep. We’ve confused a certain element

of the physical endurance—physical degradation is somehow success, right? I was just enamored and blown away by the fact that I had the chance to do it. I felt a huge obligation to not come onto a stage or into a room and tell people about how tough it was because that wasn’t the case, but come in and talk about what an incredible ecosystem it was, because to me that was infinitely more interesting. Whereas if I was going to talk about myself, what was I going to say?

How does your curiosity towards nature express itself at this stage in your life?

What I want to try and do is tell stories that create emotional context for the data that we now have. I love to spend time learning as much as I can about nature. For me, that’s where I get fascinated by every element of it. Then what I realize is we’re all hyped up on a sugary diet of likes and everything else that goes with the modern world of consumers and basically does everything possible to drive us away from having an active engagement with nature, but puts it into a voyeuristic way of viewing nature. Most of the stories that men tell are of domination, man versus nature. It’s always when animals attack, how long will I survive, how much would I get for this fish? It’s always man doing something extreme against nature. I think one of the most exciting areas for me to work in at the moment is to try and figure

What I want to try and do is tell stories that create emotional context for the data that we now have.

Photography by Martin Hartley

THE PLASTIKI

out how we can soften our relationship to nature, have more empathy, because no one hates nature yet we act like we’re at war with nature.

You’ve also started The Lost Explorer to offer sustainable products. What are you trying to achieve with the brand now?

It was always meant to be an experiment to understand: Would it be possible to tackle the concept of consumerism, is there such a thing as a sustainable brand? You start to look at things and you’re going, “But I’m making sure that’s fully organic and I’m making a shirt that’s got great natural dyes,” and then it’s flown around the world for someone to try it on and it doesn’t fit and then they fly it back again. That doesn’t make sense. That’s failing, we’re failing, and I realized that the benchmarks are really low. People are like, “Ah man that’s amazing, it’s organic, super green, well done.” No, no, no. That’s a low, low benchmark.

For many brands now, it’s becoming less about “sustainability” and more about consumption and waste. Sustainability used to be a hallmark for brands, now it’s upcycling and reusing.

When you think about environmentalism, it’s been dominated in the last twenty years by the words ‘climate change.’ Climate change revolves around energy and [people think] once we’ve got clean

energy we can do what we want, but no, we’ve got to consume less. If we’re going to consume, we’ve got to look at the model that consumption fits within, which is consumerism and the corporate model. We’re producing products excessively for newness. Newness is what drives interest and sales, and sales are what we judge success on. So I started to think, could we change the model? Could a cause actually own a company? Could nature own The Lost Explorer, and what would that look like? We’re trying to understand how to evolve the company into something that is owned by nature, and we started to play around with this idea of creating a new identity for companies that have purpose. These are the kinds of things that are just as important to me as getting onto a river and shooting awesome footage. That won’t ever stop, but I think what I’ve become aware of is actually the idea of system change is just as important as awareness and awareness is just as important as system change.

Many people try to make eco-friendly changes in our personal lives, but then reports come out saying it’s a drop in the bucket relative to the problems at hand. What do you think our personal responsibilities are? More and more, we’re in a time where we’re constantly bombarded with messages across lots of different issues and lots of different entertainment. Think about how much entertainment is being

created to keep us distracted or keep us attached to our devices with our heads down and not talking to each other. The biggest threat to our ability to keep living on this planet is apathy. We’re all very empathetic towards causes, but the overwhelming nature of the consistent flow of bad news that seems to come across is overwhelming. We become nonchalant and we go, “Well someone else is surely going to deal with this, this is too big for me to figure out.” Each of us has to take responsibility and that’s where the smaller things come in. The smallest thing you do, yes, it may be a drop in the bucket but more importantly it’s an intention. You’re still aware we need to do something and that’s really important.

Having fought for these causes for so many years only to be met with such a tepid response from policy makers, how do you remain optimistic?

There isn’t another choice. The alternative to not being optimistic is that you give up and you get back to being apathetic. I stay optimistic because I don’t want to give up, because I do believe human potential is incredible, our ingenuity is incredible, our innovations are incredible. I do believe quality of life has improved. I do believe new energy and new forms of information have the capacity to do things beyond our wildest imaginations. I think we have to find ways to organize and ways to embrace our tools, ways to embrace our creative ingenuity.

Art & Culture

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

Experiences

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

Food & Drink

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Personalities

Style

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change