Global Issue

Global Issue: Editor’s Letter

Editor’s Letter

John Fraser

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Pundy’s Picks for Conscious Travel

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Genmaicha Martini Recipe

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

The Spread Love Project by Nicholas Konert

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

Wade Davis

Anthropology is the antidote to today’s nativism says the scholar and author

Carla Sozzani

The future of retail according to the founder of legendary concept store 10 Corso Como

The Art of Migration

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

John Pawson

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Amy Duncan

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Sila Sveta

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

David de Rothschild

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Can Fashion Be Sustainable?

Shaping a better world through what you buy – or don’t

Brendon Babenzian

Supreme’s former creative director wants to end the cycle of consumption with his new brand Noah

Lily Kwong

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

House of Yes

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

Vivie-Ann Bakos

DJ Extraordinaire

Chez Dede

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

Jesse Israel

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

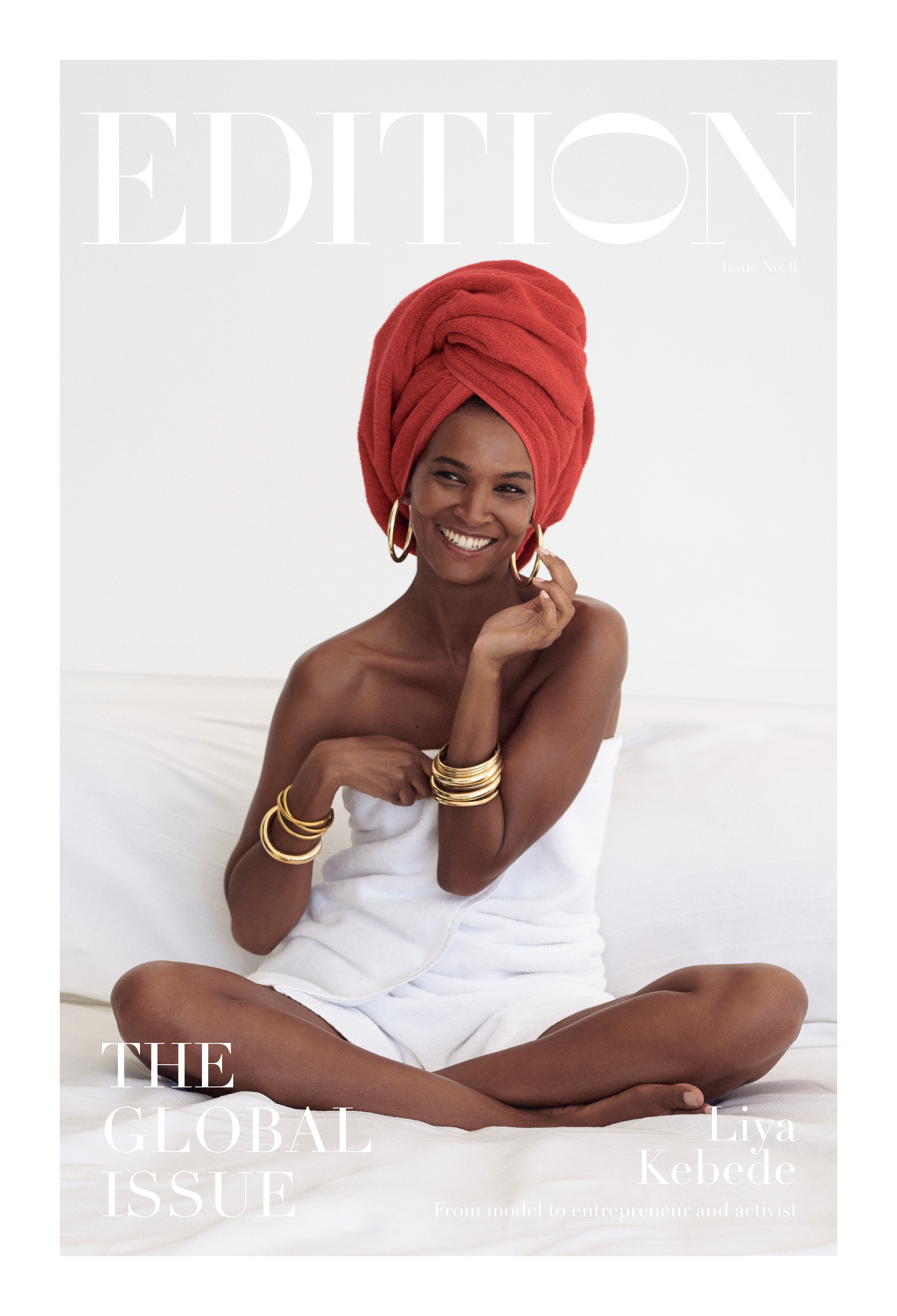

Liya Kebede

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change

WHEN YAYOI KUSAMA arrived in New York in the late 1950s, she barely knew anyone and had almost no money. A decade later, she was one of the most famous (or infamous) artists in the country. Only a few years after that, she was gone and largely forgotten.

Legend has it that Kusama arrived in New York with only the cash she was able to sew into the linings of her clothes. She was fleeing an unhappy upbringing in Japan, determined to establish herself in the city’s exploding art scene. By her own account, Kusama had begun to experience hallucinations while still a young child, for which she was savagely punished by her strictly business-minded mother. Art provided a means of escape, and she pursued it obsessively.

Kusama had already created thousands of artworks by the time she was in her twenties, and had struck up a correspondence with the famed painter Georgia O’Keefe. O’Keefe argued against the idea of moving to New York, saying the city would not necessarily be welcoming to a female artist, particularly one who barely spoke English. Kusama was undeterred, gathering up her early work, burning it at her family home, and setting out for the US.

She made connections quickly, becoming a fixture in the city’s booming art scene. She was friends with Donald Judd and Eve Hesse, had a long-running (probably sexless) relationship with Joseph Cornell, sold work to Frank Stella, and was a friendly rival to Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg. As her renown grew, she became connected to European artists such as Yves Klein and Lucio Fontana; in retrospect, her work is central to both New York’s Pop Art movement and the Zero art movement that was burgeoning overseas.

...she was one of the most famous (or infamous) artists in the country.

At the time, however, Kusama was more recognized than established. She staged public performances with naked, polka-dot painted performers at prominent locations such as Times Square, Wall Street, the Brooklyn Bridge and Central Park. By her account, these “Body Festivals” became a handy source of income for the NYPD: she paid a quick bribe and was off to perform again. She became a cover star for the city’s tabloid newspapers.

In Soho, she set up Kusama Fashion Company, selling translucent pants, tent-sized dresses and painting polka dotted outfits several decades before her recent collaboration with Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton. She named her lo the Church of Self-Obliteration, appointing herself the “High Priestess of Polka Dots,” and officiated weddings for her followers, including marrying gay couples. But she was also not well, mentally or physically, and her manic output (she was sculpting and painting hundreds of canvases a year) was bringing her close to collapse. More than anything, she wasn’t getting the nancial support that was being bestowed on her (male) peers. Invited to the Venice Biennial in 1966, she was chastised by the organizers for attempting to publicly sell the work that she was presenting.

Increasingly, her art was all there was. A lm she made in Woodstock, New York around this time is titled “Kusama’s Self-Obliteration.” For her, the seemingly ominous title could be seen as optimistic: as she told BOMB magazine in 1999, “By obliterating one’s individual self, on returns to the infinite universe.” Looking back at her legacy, Kusama seems to see herself as both marginal and vast, like the tiny dots that cover one of her massive canvases.

By the early ‘70s, Kusama had essentially disappeared. For nearly a half-century, she has lived and worked at a mental health facility in her native Japan and for many years it seemed like she might be forgotten completely. Instead, now 80 years old, Yayoi Kusama is the top- selling female artist alive.

Perhaps more than her individual works of art, it is Kusama’s tricky, multifaceted public persona that continues to resonate and inspire admiration. Along with Warhol, she was a pioneer in redefining the role of the artist from essentially an elevated craftsperson—a painter or sculptor, for example —into a personal brand and multifaceted creative enterprise. What confused critics at the time— her refusal to focus on one genre, the brightly appealing repetitiveness of much of her art, her willingness to turn herself into a spectacle— now provides an accurate description for the formula behind becoming a star artist.

And despite her reclusive residence, she also maintains a high profile in the art world—at museum openings, she appears in brilliantly eccentric outfits, sporting a garish red wig that would shock even Warhol. As he could have told her, sometimes you have to recede in order to bring your audience closer. Her latest exhibition will be on view at David Zwirner through mid-June. It might be wise to get in line now.

Yayoi Kusama in her 2013 solo exhibition “I Who Have Arrived in Heaven” at David Zwirner, New York. Image © Yayoi Kusama. Courtesy David Zwirner.

Art & Culture

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

Experiences

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

Food & Drink

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Personalities

Style

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change