Global Issue

Global Issue: Editor’s Letter

Editor’s Letter

John Fraser

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Pundy’s Picks for Conscious Travel

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Genmaicha Martini Recipe

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

The Spread Love Project by Nicholas Konert

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

Wade Davis

Anthropology is the antidote to today’s nativism says the scholar and author

Carla Sozzani

The future of retail according to the founder of legendary concept store 10 Corso Como

The Art of Migration

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

John Pawson

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Amy Duncan

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Sila Sveta

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

David de Rothschild

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Can Fashion Be Sustainable?

Shaping a better world through what you buy – or don’t

Brendon Babenzian

Supreme’s former creative director wants to end the cycle of consumption with his new brand Noah

Lily Kwong

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

House of Yes

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

Vivie-Ann Bakos

DJ Extraordinaire

Chez Dede

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

Jesse Israel

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

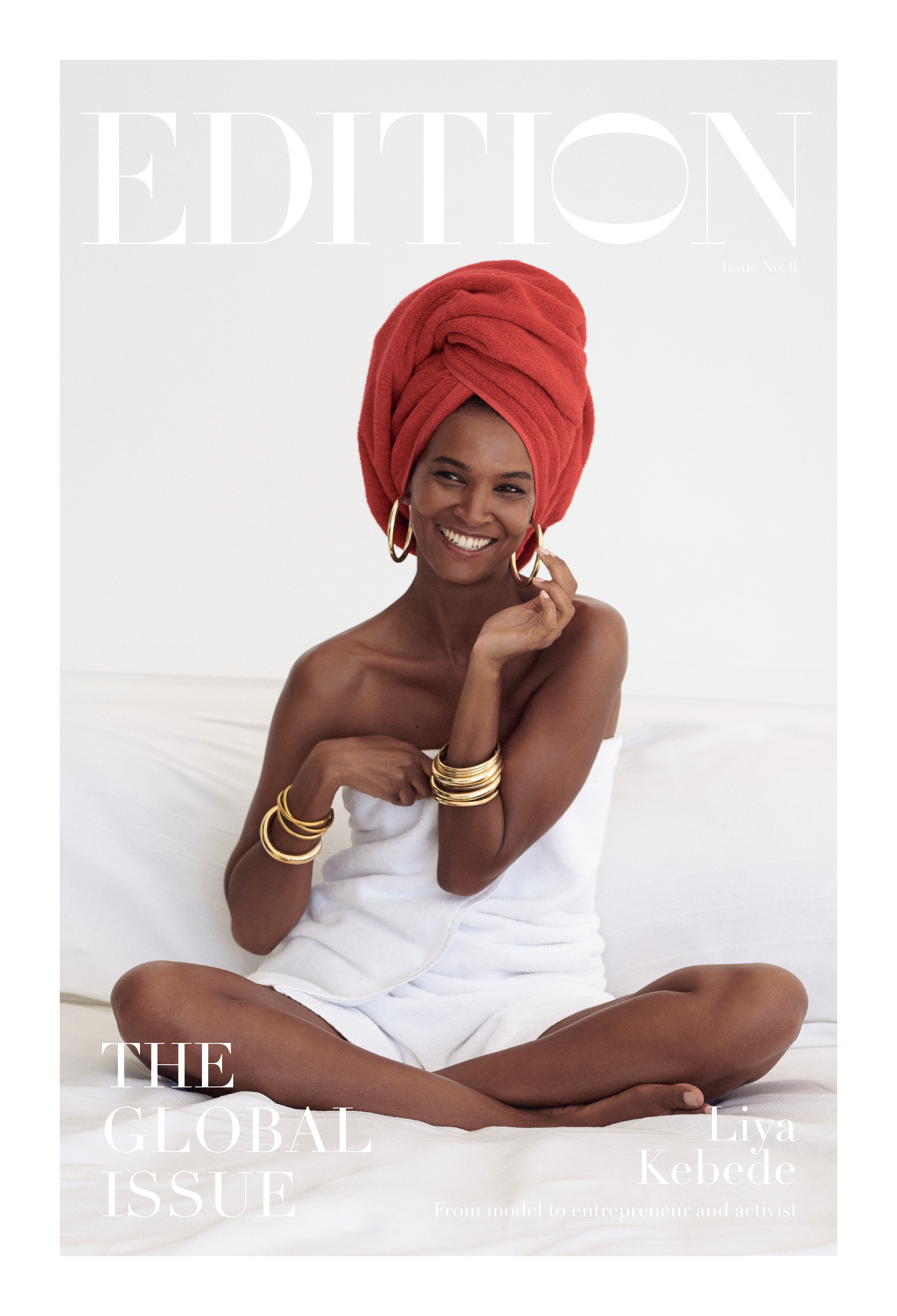

Liya Kebede

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change

Marc Benecke

Confessions of a Studio 54 Doorman

Illustration by Stefan Knecht

In the three short years of Studio 54’s heyday, Marc Benecke was who you had to get past to enjoy the hedonistic other side. Opened by Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager in 1977—the same year Saturday Night Fever came out—there’s never been a club like it since, with celebrities, socialites and scene- makers clamoring for a ticket in. If Benecke granted you entry, you were whisked through the “Corridor of Joy,” a long hallway echoing screams of happiness before partygoers melted into the eye of the disco storm, Studio 54’s dance floor. After it all came crashing down and the club closed, Benecke took a much-needed West Coast hiatus. He’s now back with a Studio 54 radio show on SiriusXM and a new position with Schrager, as the New York EDITION’s night manager.

I imagine your role at EDITION will be more tame than working the door at Studio 54.

Absolutely. It’s much more adult. Not that Studio wasn’t adult. I think the Village Voice put it best when they said you can’t reheat soufflé, and that’s basically what the story was at 54. It was of the times, of that moment.

What was the celebrity culture like back then?

It was before cell phones and before TMZ and all the media outlets that we have today. People Magazine was barely three years old when Studio opened. And Entertainment Tonight, the first show on TV about entertainment, didn’t even start until ’81, ’82, when they had already sold Studio. ” Page Six” was around, though! [laughs] The Post was already doing its thing back then. It was as important to be on”Page Six” as it is today. Therefore, celebrities and people in general were willing to let their hair down a lot more. And not everybody had an entourage. I mean, we had major stars like Elizabeth Taylor, Warren Beatty, Jack Nicholson, Mick Jagger. But no one ever came with anybody other than themselves and whomever they were with. And people felt incredibly comfortable there—because we did the selection process at the door.

At 19 you were one of the youngest on staff at Studio 54. How did you get involved at such a young age?

A distant cousin of mine had a bouncer contract for 54. I was having lunch with him and he was like, “What are you doing the rest of the day, how’d you like to come over to this new club we’re doing security for?” We walked over there and I got interviewed by Steve Rubell. He asked what I was doing for the summer and was like, “How would you like to work here?” And I’m like, “Okay.” That’s basically how it started!

Were you interested in the club scene then?

Not at all. My mom came from a political family. They were very into social issues and I grew up being politically aware at a very early age. I was a poli sci major in school, I wanted to become a lawyer. I had only ever been to one club—I wasn’t interested in that whatsoever. And I just got opened up. Steve liked the fact that I knew nothing about the whole nightclub scene. He basically taught me everything: what to look for, what not to look for.

Some of the social and political issues of the time must have played out at Studio 54?

54 was like the window right after the Vietnam War ended and right before the AIDS epidemic took hold, so there was like this three-year window where people just had a crazy time. It was pretty awesome. People were really tired of war and people just wanted to have a good time, and we did.

At the door, Steve Rubell tasked you with letting a “mixed salad of people” into the club. How did you do that?

There were people that were just flat-out fabulous, that would get in no matter what. But even if you worked at McDonald’s and you liked to come and just dance, and you had good energy, you could get in. You had a really interesting mix of all different levels of society. In that way it was exclusive but also inclusive. People got off on that. If I can be emotional for a second—one of the things I think that made me a good doorperson was that I can really feel [people’s] energy and for the most part, where they’re coming from.

What was your approach to turning someone away?

Steve had this amazing talent to converse with anybody and make you feel like he was your best friend. He was able to turn people away with a smile. I wasn’t good at that, because in some ways I’m naturally shy. So if I wasn’t going to let someone in, I just didn’t engage. That probably kept me out of a lot of stuff. People see you as arrogant, whereas for me it was more of a self-defense mechanism.

I heard you would tell people who were desperate to get in to go buy the same jacket that you were wearing and then you’d let them in?

I was very young. I could never do that job now. This was like a different person. Yeah, I actually told this one guy to go buy this blazer that I had on at Bloomingdale’s. He went and did it and I still didn’t let him in. The outside was really a show in itself. When people got to know me, they realized I wasn’t like that…

But you did have the power position.

I definitely did. The Times said I was the socially most powerful person in New York.

You must have met a lot of amazing characters at the door. Who do you particularly remember?

We had this guy named Rollerina. He worked on Wall Street and he used to dress up in this semi-drag outfit. He was like a fairy godmother. He used to hide his costumes in different nooks and crannies in the city because there was no way he could change—especially in those days—from his job on Wall Street. He was like Superman, hiding and putting on his costume in a phone booth.

A lot of art-world personalities went to Studio 54, but was Studio 54 a part of the art world?

To an extent. Andy Warhol was one of the few well-known artists in the world [that came to Studio 54]. And there was the whole Basquiat, Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf [crowd] in the 80s, which the Palladium action was also a big part of. But at Studio, it was limited—Paloma Picasso used to go there, Salvador Dalí. He had this drag queen muse…

Was Andy Warhol really shy?

Yes, very much so. He would say very few words. He’d have dinner in fairly large groups and you could get a sentence out here and there, but in general, he was more of an observer than a participant unless he knew you really, really well. It’s fascinating that he could create this whole empire around him while being so reserved. What was wonderful about Andy was that he always encouraged people, especially people who moved to New York and were interested in being involved in the arts. People told me they’d say, “I can’t write this,” and he’d say, “Oh, of course you can.” I think that was a huge part of the allure, that people felt comfortable [at the Factory].

New owners took over Studio in 1980. How different was the vibe once Ian and Steve left?

Much different. The city had moved on. The music scene was different—’81 was that New Wave, New Romanticism era of music, groups like ABC and A-Ha and punk by that time as well. The whole disco scene really wasn’t what was happening at the moment. And then they redid the Palladium, and that was happening.

Many of the people that you worked with at Studio 54 got burned out on the industry because of all of the excess. Was it as extreme as its been written about?

It was as crazy as has been talked about. Back then it was kind of normal for people to be excessive. People functioned that way. Not everyone, not really me either. Nobody believes that so I never say it, but I didn’t experiment until I moved to California. But people stayed out ‘til 4:00 in the morning and then they went to their job. Instead of doing a Red Bull they would do a line. That’s really what happened. It wasn’t all over the place. But people who were in the main industries of New York, finance, fashion, entertainment, it was considered normal. You would offer somebody a line, like somebody would get offered a bottle of water today.

This may sound naïve, but were people happy back then?

We’ve been on this long journey to figure out what happiness is. At that moment, people felt like they were happy because there were so many more people going along for the ride. People felt like the key to happiness was maybe not getting married, but maybe having multiple partners. So people felt that that life could be happiness. Of course you had a lot of people burning out and most unfortunately, a whole lot of people died. But I think people were happy.

Art & Culture

The power of art to inspire empathy and social action

Zen Buddhism and minimalist purity drive the celebrated architect

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

A medium in which two world-traveling, adventurous spirits absorb the globe’s vast curiosities and share them freely

A meditation guide for extraordinarily large groups

Experiences

Moscow’s favorite media studio finds the perfect balance between art and commerce

In his calls for environmental awareness, the modern explorer finds harmony between man and nature

Behind the scenes with the Bushwick nightlife collective promoting inclusivity and consent culture

DJ Extraordinaire

Food & Drink

The Michelin-starred chef has a story to tell you through his cooking

Six tips for considered and conscious travel

Personalities

Style

The classic martini plus the health benefits of green tea

How Nicholas Konert’s rainbow heart design became an international icon

As the CBD line Mowellens expands into skincare, its founder shares the personal story behind her company

Nature invades the urban jungle in the landscape designer’s expansive projects

The Ethopian model, activist, and entrepreneur uses her label Lemlem as a force for change